Another Predictive Analytics Times Post:

Will there be enough data scientists in the future? The question sounds like a subplot for a science fiction film, but it has received much attention over the past few years due to the forecast of a substantial shortfall in the industry. A McKinsey study has projected that “by 2018, the United States alone could face a shortage of 140,000 to 190,000 people with deep analytical skills.” This deficit is making it increasingly challenging to hire data analysts; because of their rarity, they are now beginning to be described as unicorns. A recent article even magnifies the issue by calling them purple unicorns, and another argues that we are looking for a data science platypus because we do not know what we want.

Predictions are difficult to make, especially about the future, but it is helpful to quantify the problem. As data scientists and companies seeking to hire data scientists, we should break down this anecdotal deficit notion to see what it means. Data Science is not a new concept; while the term is new, people have been performing these tasks for many years. So, we must ask ourselves if the deficit is related to the number of people available, or if the problem lies in how we define a Data Scientist.

A Data Science seems to mean one with the full range of skills that could be needed in the industry, making it challenging for a company to find the right talent and nearly impossible for one person to have every skill required. Additionally, as new technologies emerge every year, the definition broadens; a perfect fit today may not have every skill required of a new hire a year from now. What’s the solution? Finding 200,000 people who can use Hadoop is a challenge, as it is still a somewhat new technology; however, finding 200,000 analytically-driven people is a different matter entirely. It could be that the deficit will shrink substantially if we simply temper our expectations and allow people the time and training they need to acquire new, specific skill sets.

The challenge of defining roles in a developing industry isn’t new. It has already appeared in the software industry, but eventually different labels were converged upon to define different roles. Front-end staff work on the parts of software that people see (javascript/html/css) and back-end staff work with servers and performance (java/scala), while full-stack employees have some knowledge in a lot of areas. Data Science is beginning to settle on different roles as well, as we can see in an excellent article by a member of the Twitter team. The article splits the industry into Type A (statistics-focused) and Type B (engineering-focused) Data Scientists. There has also been the growing but dwarfed effort to tag this Type B role as a “Data Engineer.” Another excellent article, Analyzing the Analyzers, attempted to define new categories by looking at what Data Scientists really do, resulting in roles that real humans can fill. One of its goals was to change what hiring managers were asking for and how they crafted job posts. Did their methods work? Are companies asking for too much, maybe even everything? Is the deficit a result of expecting skills few had had time to develop? These questions are essential to answer to define realistic roles within the industry. Despite these articles, however, many companies have not yet adopted new roles or updated their job responsibilities.

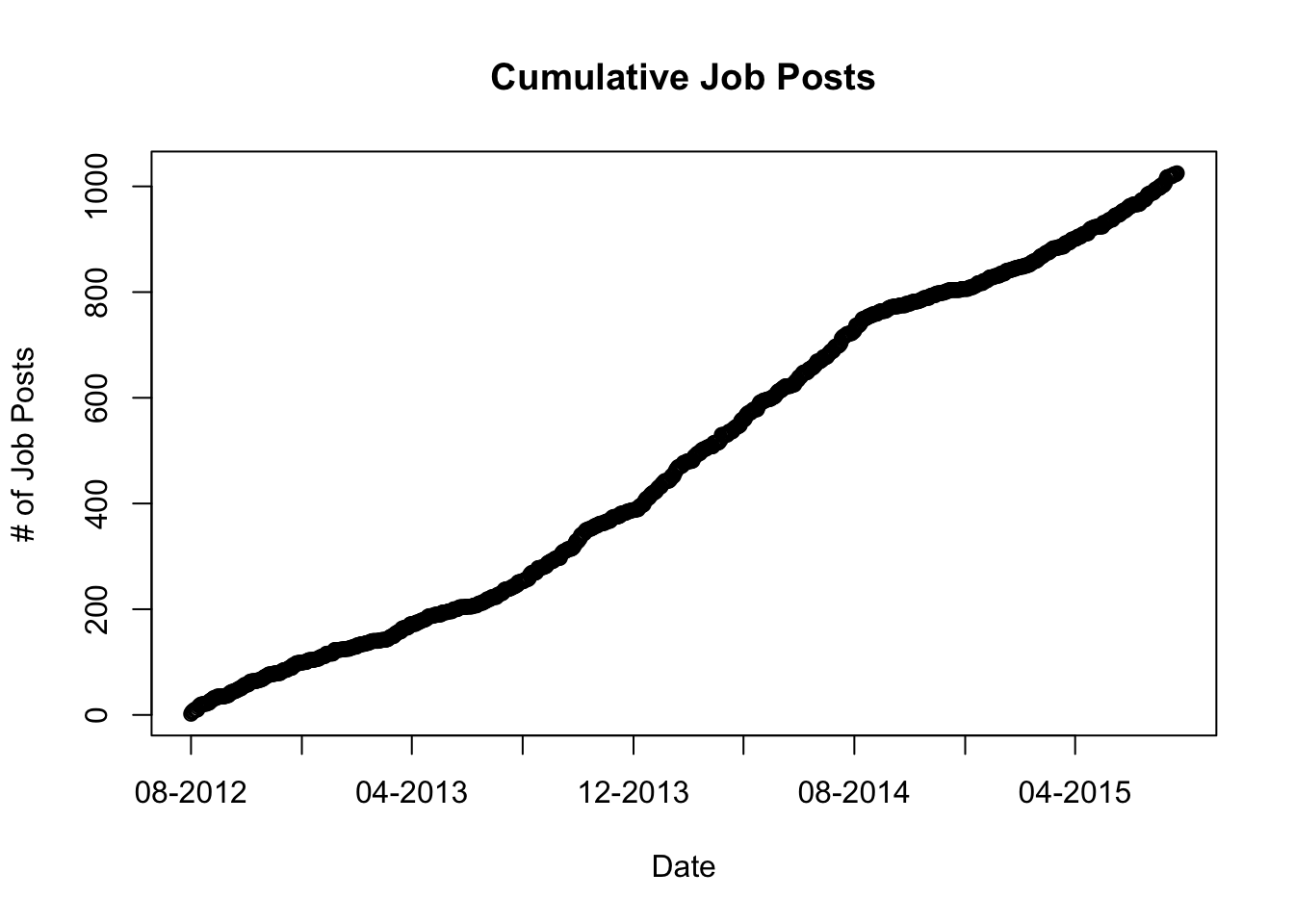

Sherlock Holmes claimed, “It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts.” To adhere to this rule of one of the first Data Scientists, we need some data before we continue theorizing. On second thought, before we label Sherlock Holmes a Data Scientist, we need to determine whether he was proficient in the ways of Hadoop and Spark, had a PhD Statistics with nine years of DBA experience, and could write efficient code object oriented and functional code for the Babbage Engine. But I digress. The data we will use to examine this problem includes about 1,000 job postings for Data Scientist-related positions over roughly three years.

The postings are pretty uniform over time to avoid over-emphasizing any period more than any other. Our first step is to ensure that these postings are related to our discussion. To examine this, we can look at the position titles for the postings.

## title number

## 1 data scientist 476

## 2 engineer 142

## 3 analytics 119

## 4 analyst 118

## 5 learning 66

## 6 machine 65

## 7 research 60

## 8 software 48

## 9 big data 39

## 10 business 32

## 11 predictive 29

## 12 statistician 27

## 13 modeler 27

## 14 developer 22

## 15 quantitative 20

## 16 architect 19

## 17 intelligence 17

## 18 mining 9

## 19 database 8

## 20 hadoop 8All of these terms are related to the field of Data Science. We can see from the data that many companies are starting to ask for more precise roles. While all of the jobs are related to the field of data science, some may be asking for a software developer or system architect; however, the go-to term still seems to be Data Scientist. What type of experience are companies looking for?

## level number

## 1 senior 102

## 2 principal 14

## 3 manager 65

## 4 lead 47

## 5 junior 14

## 6 director 19An important observation here is that significantly more people want senior staff than junior Data Scientists. This is part of the problem: many companies are not willing to train people or allow them to learn on the job.

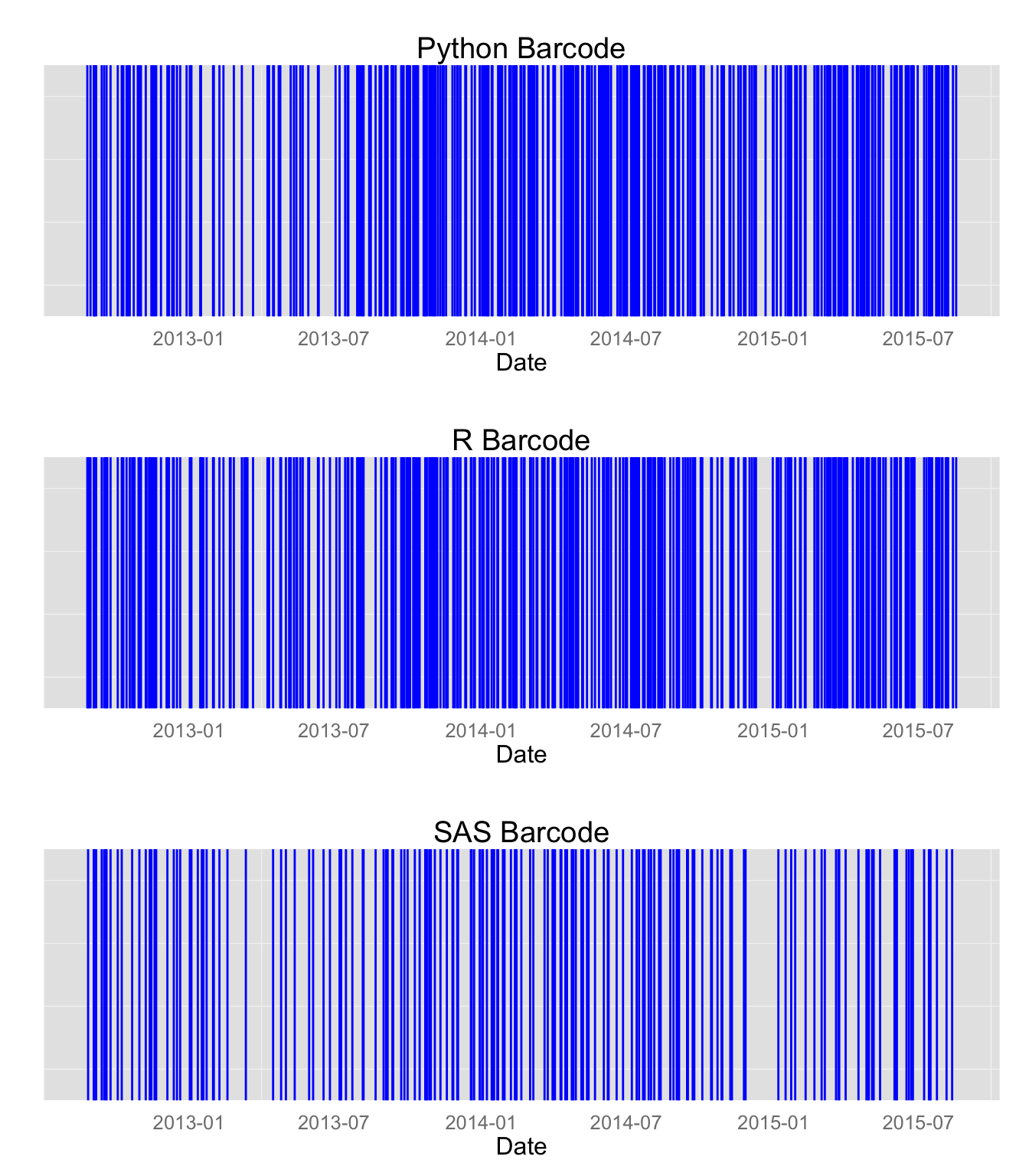

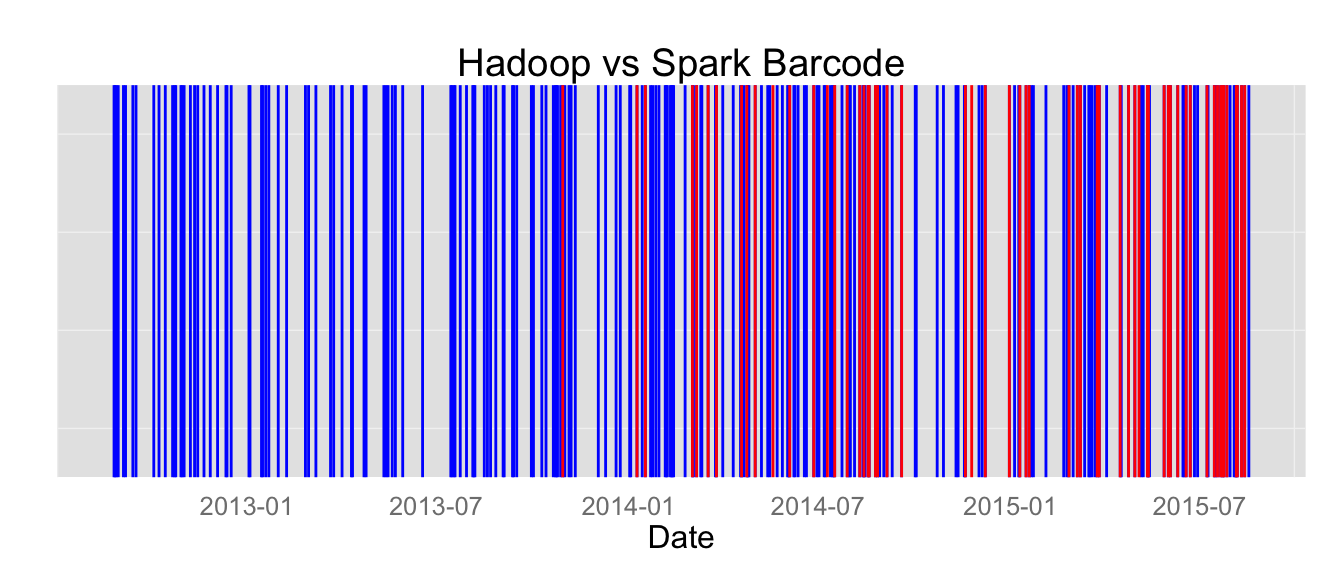

These charts don’t show us how requirements have shifted over time, so the barcode plots below show vertical lines for each day that a post requested that skill.

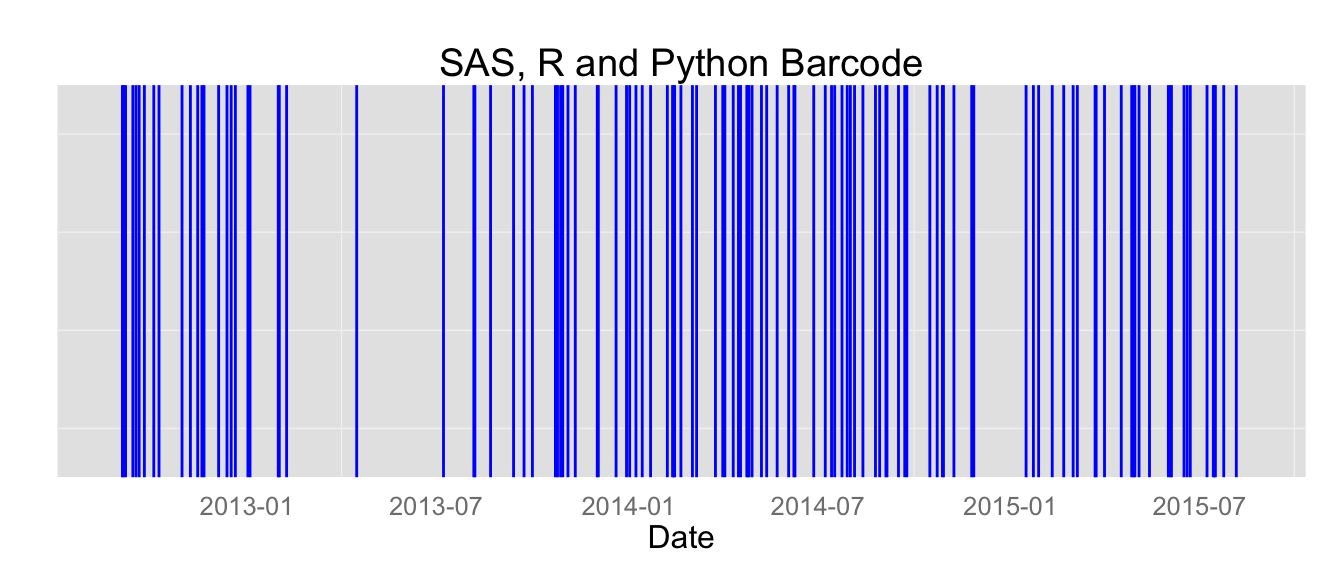

Python and R are very common job requirements, and SAS is often mentioned as well. The next question is: how many jobs ask for all three of them?

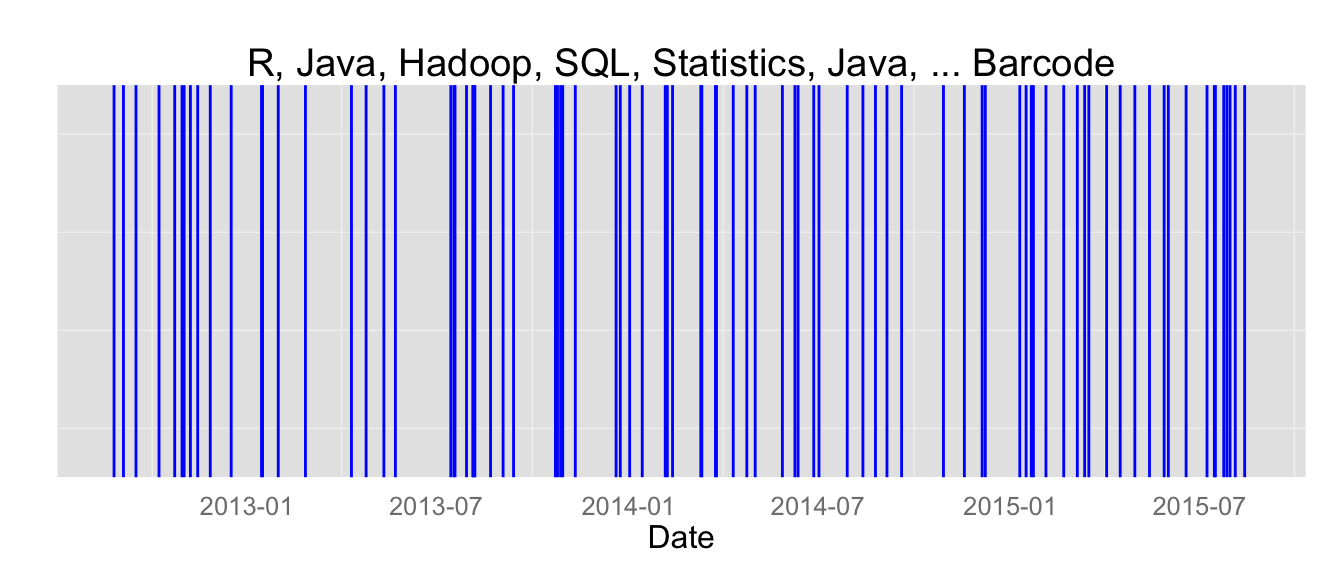

This chart looks very similar to the chart showing job descriptions only mentioning SAS. For many companies, if you want a Data Scientist with one of these skills, you ask for all of them. It would be unfair to say this is a bad thing; companies could be acknowledging that if you know one, you can quickly learn the others, rather than requiring knowledge in all three. To be certain, we would need to know if the post asks for ‘Python, R, and SAS’ or ‘Python, R, or SAS.’ Since this is a relatively minor difference, we will give them the benefit of the doubt. What is more concerning is what happens when we throw statistics, SQL, Hadoop, and Java into the mix, as you can see in the chart below:

Companies appearing in this chart aren’t really looking for a specific candidate they need: they are looking for everything and the kitchen sink. They know that their data needs will evolve and become increasingly important, so they want to have people in place who have exposure to all the current languages of data science. The result of this trend is that companies who require experience modeling Hadoop may not even use Hadoop; they know that having these skills in their talent pool could help them in the future. It is a good strategy to look for someone who can do a bit of everything; however, when it comes to the way jobs are posted, what solicitations are calling for, what managers say they really want, the position requirements aren’t reflecting the true needs of the client.

The data supports our claim that companies are not using well-defined roles in their job descriptions. The next question is, “How relevant are the skill sets currently required by hiring managers?”

The Spark vs. Hadoop plot is very telling - it demonstrates how quickly specific skill set requirements are evolving. Even if we find a purple unicorn today, six months from now we need a green unicorn, or maybe even a Pegasus or a dragon. This leads to a different problem: Data Science encompasses many tools and skills that do different things, and companies are seeking different collections of those skills based on both current needs and projected future needs. However, people often have unique combinations of skills rather than fitting cleanly into these job descriptions. For example, if you need somebody to build a production recommendation engine, you may want two staff members: a data scientist to analyze the data, find the segments in users and products, and create some hybrid of content-based filtering and collaborative filtering; and a data engineer to collect and process new data and provide recommendations to users in a consumable way. However, building a production recommendation engine requires seven or eight unique skills, and it would be a poor assumption to think that we could divide this evenly among two people. Each person has a set of skills that he or she has picked up from different roles. Strategic candidates will have attempted to fit the unicorn persona and expand their learning to disparate areas; however, they may have some of the analytics skills needed and some of the engineering abilities. Finding a second person to exactly fit the remaining skills gaps may require another data scientist just to work on the optimization problem.

Here is better view of how these skills have changed over time. You can modify the contents and use it more interactively:

Every software engineer, no matter how good, was originally trained in how to write code. The same goes for statistics; it was taught. Technical skill sets can be taught; they don’t need to be already mastered in every new hire. As new tools are required, we should acknowledge that we can train people to use them. We should also realize that we need a team of people to work on complex problems rather than one person who knows everything.

Sherlock Holmes claimed the mind has a finite capacity for information storage, and learning useless things reduces one’s ability to learn useful things. When he learned that the earth revolved around the sun, he immediately set out to try to forget it since it was not relevant to his work. The skill sets companies seek are far from useless, but the principle remains: no one person can possibly do it all.

Much like your stock portfolio, you have to diversify. Today, the ideal Data Scientist is one who has experience with a little bit of everything in an IT space that is still evolving. They are a purple unicorn, born from a Pegasus mother and a Minotaur father. It’s possible that Data Science will become increasingly specialized, much like software engineering, but for now, diversification is the name of the game.

If you hire a diverse team of excellent people, they can develop the skills that are valuable to your business. Otherwise, you may spend some time forcing them to forget some things. So, if technical skill sets shouldn’t be the primary requirement, what should be? The answer is simple: as a company seeking Data Scientists, you should look for skills that cannot be taught. Qualities like curiosity, tenacity, skepticism, and empathy will get you farther as a team than expertise in Hadoop (especially if the candidate lacks those soft skills). If you’re curious about the research surrounding the importance of soft skills in Data Science, the links below will allow you to dig deeper.